|

|||

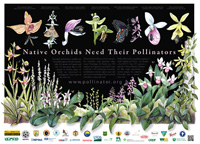

THE ORCHIDS Orchid flowers are unique. Their male organs (one or two anthers) fuse to the back of the female organs (pistils). Both sets of organs work together to transfer pollen to a visitor and then collect it again when the insect enters a second flower encouraging cross-pollination. With the exception of milkweeds (Asclepias) and their allies, orchids are the only plants on this planet that release their pollen as discrete balls (pollinia) and each ball may contain thousands to millions of compacted grains. As the pollen-accepting tip (stigma) of an orchid has space for only a few pollinia this means that, quite often, all the seeds in the same orchid pod have the same father flower. The successful transfer of pollinia then makes all the difference between orchid motherhood and extinction. Lots of animals visit orchid flowers but each orchid species often has “preferred” pollinators. An orchid flower that is pollinated by queen bumblebees has a floral architecture that makes it improbable that visiting moths or butterflies will pollinate it no matter how hungry they are. Around the world different orchid species may be pollinated by different members of seven different families of bees, several families of wasps, nectar-drinking flies, butterflies, sphinx and settling moths, hummingbirds and African sunbirds. No bat-pollinated orchids are known to date but on the island of Reunion, in the Indian Ocean, at least one species (probably more) night-blooming orchids is pollinated by a raspy cricket. |

In North America, we see only a few orchids pollinated by hummingbirds in Mexico. All remaining species are pollinated by insects, but that can include some rather unusual creatures including clear wing hawkmoths and mosquitos. Once we enter the warmth of Mexican forests we find hundreds of species of specialized bees in which the males visit orchid flowers to collect perfumes. They use these scents to mark their territories and, more often, they make colognes that will attract other males. These males hold massed mating displays (leks) attracting females. These tropical orchid bees receive their own tribe, the Euglossini. Recently one of these “orchid bees” established itself in Florida. In the 19th century wealthy people started collecting tropical orchids for their new greenhouses and they dissected the flowers. Amateur botanists were perplexed. Why did they have such unusual shapes and why did male and female organs fuse together to form a reproductive structure they called the column? Charles Darwin observed wild orchids around his home in Kent, England for 20 years, but also received and studied plants from the tropical Americas and Africa. He published his findings in 1862 and revised them in a second volume in 1877. Read it today and you can see how he came to the conclusion that the unusual forms of the flowers were adaptations that helped transfer pollinia between flowers when insects came for nectar or other foods. He noted, for example, that different orchids deposited their pollinia on different part of different insect bodies. Butterflies and moths still tend to carry the pollinia at the bases of their tongues while bees and wasps are more likely to carry them on their heads or backs (often between their wings). At times, Darwin pretended he was an insect inserting pencil tips, pins and straws into the flowers and then removing them to see if he had withdrawn the pollinia. To help prove his points, Darwin employed a scientific illustrator (G.B. Sowerby) to draw the interiors of dissected flowers, changes in the pollinia as they dried and a moth head wearing pollinia at the base of its tongue. |

||||

What Darwin didn’t know is that many orchids trick insects into pollinating the flowers. The color and odor of some orchids looks enticing but there’s absolutely nothing to eat inside and no perfumes worth collecting. For example, all of our lady’s slipper orchids (Cypripedium) do this whether they are pollinated by big, queen bumblebees (C. acaule),or tiny sweat and halictid bees (C. arietnum).

|

||||

All orchid species that are cross-pollinated must have an animal pollinator (no wind or water-pollinated orchids) but no pollinator is entirely dependent on orchid nectars or perfumes to survive. Even those male orchid bees that must collect scents to reproduce have the option of shopping for chemicals from the resins and leaf and tree bark or from completely unrelated flowers like tree tomatoes (Cyphomandra) and flamingo tongues (Anthurium). Orchids must compete for pollinators, especially the ones they trick. This competitive mode has been unusually successful as the family of orchids is one of the largest in the world. There may be over 20,000 species on this planet as new ones are described monthly. Some botanists speculate that one out of every 10 plant species on the planet is an orchid but the vast majority is found around the equator. Distribution of orchid species in North America seems unfair without a big tropical zone. Mexico has over 700 species but the continental United States has only 100 and Canada just 30. The good news is that some orchids really like cold bogs and tundras, so you can find over 25 species in the brief summer of the Alaskan panhandle onto the Kodiak and Aleutian islands. Orchids need their pollinators even when their pollinators don’t always need them. As we can see, though, many North American orchids and some pollinators have grown increasingly rare. Extensive colonies of riverside and valley orchids seen by Henry David Thoreau and John Muir in the 19th century are harder and harder to find, just like the bumblebee, Bombus bimaculatus. To help protect these species, please don’t pick the plants or try to transplant them (they won’t survive). Refrain from buying tropical species from Mexico or Florida unless you know their seeds were grown in a greenhouse or by cloning potted plants (man-made hybrids are fine). If you find them on a hike why not share them in photos? You can help scientists by photographing pollinators at the flowers and reporting the populations you find to botanic gardens, the US Forest Service and to plant biology departments at local universities. |

||||

Orchid Identification

While there are more than two dozen helleborine orchid species in Europe, Asia and Africa our stream orchid, E. gigantea is the only Epipactis species native to North America. Yes, we do have a few populations of Epipactis helleborine in northeastern America and Canada but it seems to have been introduced accidentally from Europe. We also know our E. gigantea as the chatterbox and the giant helleborine. Its hinged, striped, lip petal may bounce up and down on breezy days making the tip of the petal resemble a wagging tongue. Compared to the helleborines of the Old World it really is a giant producing a stem that can grow 3 ft high. The plants appear to do well among sand, gravel and stones along creeks and riversides. Some populations actually seem happy and robust around hot or even salt springs. |

Also known as fragrant orchid, scent bottle, white northern orchid, white rein orchid and bog candles. Like most orchids there is only one pollen box (anther) in the center of the flower but it is so broad and flat scientists named the entire genus Plat = broad and flat, anther = anther. A single flowering stem of bog orchid may bear a hundred flowers with most of them open at the same time. Some people say they smell like cloves. Native people living in Alaska and Canada dug them up, boiled the starchy underground storage organs (tuberoids) and ate them like potatoes. |

There is only one species of Galearis orchid in North America and our wildflower is found from southeastern Canada, through New England extending through the American Midwest and just south of the Mason-Dixon line. Canadian and New England plants may bloom as late as July while those in America’s southlands can be found as early as mid-April. A cousin (Galearis diantha) is found in China. Flowers are rarely pure white and usually wear a pink-purple to rich reddish purple “helmut” (galea = helmut). While some plants bloom in old fields most appear to grow best in moist, wooded ravines with trilliums and jack-in-the-pulpit. As this species becomes increasingly harder to find local naturalists may be able to show you some plants if you refer to them under their other common names including gay orchis, purple orchis or purple-hooded orchis or even two-leaved orchis. The lip petal has a hole at its base leading to a hollow spur that containing a droplet of nectar. The queens of at least five bumblebee species drink the nectar of this orchid and pollinate the flowers. In Canada, though, the most important pollinator may be a smaller orchard bee (Osmia proxima). |

Found in bloom from June through August in wet forests of pines and other conifers. It also likes cold, sphagnum bogs and true tundra. While we think of this wildflower as a summer plant of Alaska, Canada and New England the exact same species is also found in Siberia, northern China and Asian countries that were once part of the old Soviet Union. Their skinny stalks rarely bear more than 15 flowers. Female mosquitos aren’t the only pollinators of these little, green-flowered orchids. They are also pollinated in part by small, nectar-drinking, snout mouths (pyralids). |

Botanists recognize over 30 species of Platanthera orchids in the United States alone but the large-flowered species with the sweetest scents and fringed petals prefer to grow in seeps, swamps and sphagnum bogs and are the favorites of hikers (especially when the bloom en masse). Botanists often fail to agree about how to identify these orchids to species especially plants bearing pink to purple blooms as they have a history of hybridizing with each other and to Platanthera species with white flowers. Platanthera shriveri is a controversial “new species” of the Appalachian mountain range, first described in 2008. While people have been studying it since the 1990’s it was not recognized as a real species in Volume 26 of Flora of North America (2002). Some treat Shriver’s frilly as a late flowering form of Platanthera grandiflora. Others suggest it is one of several populations of hybrids between one of the purple flowered Platanthera species and the whitish-green P. lacera. These naturalists contend that Shriver’s frilly orchid evolved from hybrid stock by a process of backcrossing between hybrids and parent species (properly known as introgression). Whatever the case, Shriver’s frilly remains popular with large butterflies as a nectar resource. Some scientists suspect that the fringes and frills on the species of Platanthera with large, colorful flowers represent hidden perfume glands (osmorphores). |

The Swedish botanist, Linnaeus, must have loved the colorful, pouched labellum petal of slipper orchids as he named the genus, Cypripedium, in honor of the beautiful, slipper wearing feet of Aphrodite (the patron goddess of Cyprus). Therefore, it shouldn’t surprise us that C. reginae is also the queen lady’s slipper (regina = queen). There are at least 13 slipper orchid species found from Canada to Mexico. Our showy lady’s slipper has the third largest petal sac (labellum) in North America after the more common pink slipper (C. acaule) and the even rarer Mexican, pelican flower (C. irapeanum). Our showy slipper may be found from eastern Canada through New England and much of the eastern seaboard westward through our Great Lakes and south into Missouri. It is the state flower of Minnesota and the provincial flower of Prince Edward Island (Canada). It prefers to grow in bogs or along trickling creeks and mossy beds that remain moist at least during mid-spring. Unfortunately it has also grown increasingly rare due to habitat destruction and vandalism. The beautiful sac is devoid of nectar and, like all slipper orchids studied since the early 20th century, it lures insects into its “pouch” with vivid colors and false promises. The Showy slipper specializes in deceiving medium-sized bees like the Anthophora abrupta and various members of the leaf cutter bee family (Megachilidae) while the pink lady’s slipper tricks queen bumblebees. Recent gene studies confirmed that the showy slipper has a “sister species” in China but is has yellow flowers (C. flava). While our showy lady’s slipper does have a fragrance human beings find it faint or odorless as our noses are not able to pick up low concentrations of methyl salicylate (wintergreen oil). |

Yes, this is the wild version of the domesticated vine whose fermented fruit gives us the flavor of vanilla. The Aztecs appeared the first to combine their chocolate with the essence of fermented vanilla pods and other herbs to make a beloved beverage that the Emperor Montezuma supposedly served to the conquistador Cortez. Mexico continues to export vanilla pods commercially but, the vines were exported to other countries over the centuries, (including Madagascar) and trained workers always hand pollinate the flower with sticks to maintain the highest yield of pods. This must be done quickly as, unlike so many other wild orchids, the blossoms of vanilla rarely live for a full 24 hours (only 8 hours for some flowers). Old stories insisting that this flower is pollinated exclusively by the Mayan honeybee (Melipona beechei) are incorrect. Based on a study published in the journal, Lindleyana in 2006, V. planifolia depends on several species of medium-sized to large, orchid bees in the genus Eulaema. To clarify, Eulaema cingulata, E. polychroma and E. meriana, as well as Euglossa viridissima and Melipona beecheii (Mexico) are commonly found in Central America and northern South America to pollinate the vanilla orchid. |