The following are opinion pieces developed by partners of NAPPC (North American Pollinator Protection Campaign). They are opinions expressed by the author. If you have any comments, please direct them here.

| Search by title: |

Conservation of Native Pollinators on Golf Courses

These golf course habitat areas for plants and insects also offer educational possibilities, not just for the golfers but also for local schools and communities who can learn about practical conservation techniques and witness first-hand their benefits. Conservation of native bees and plants is a valuable way in which golf courses can contribute to a healthier environment, and is a simple task to integrate into the management of a course.

Additional Information: |

|

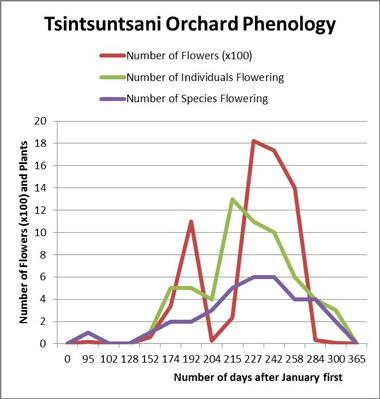

When You Plant Flowers This Spring, Think Pollinator Forages, Phenologies and Partnerships More than ever before, Americans are looking at their planting of flowers on their land in their gardens in a broader context, one that includes colors and fragrance, but extends beyond our own perception of those attractions to how pollinators themselves perceive them. The reason for this paradigm shift is obvious to anyone who has been reading the news of hearing it on radio and TV: the numbers of monarch butterflies, bumblebees and honey bees this last year have been lower than at any time during our own lifespans. Some migratory pollinators such as monarchs and hummingbirds have also arrived in the United States only to find that their arrival times are mismatched with the onset of flowering of their favored nectar resources. These mismatches pose risks to the nutritional health of the floral-visiting migrants, but they warn us that climate change may be disrupting long-term partnerships between native plants and their most allegiant pollinators.  Now compare the duration of nectar availability in the above graph with that available in a recently-planted but still immature hedgerow:  The second graph shows that plantings have already increased the availability of nectar resources during mid-summer but have not yet had much effect on promoting more flowering during the spring drought period in southern Arizona when nectar availability may be extremely limited, which may become more of a problem with intensified climate change. During this period, fewer kinds of native wildflowers are in bloom, but many of them now bloom for shorter periods of time. This leaves “phenological gaps” in flowering times just when hummingbirds, monarchs, bats and white-winged doves return to southern Arizona in large numbers. Three springs ago, a Rufous hummingbird arrived in a wolfberry bush in my orchard, weighing half of what it might have normally weighed in a year of abundant spring rains and ample flowering along its migratory corridor. It died in my hand, perhaps because of the lack of floral resources over the six hundred miles of its migratory corridor immediately south of my home, for plants along that corridor had been killed or damaged by both drought and catastrophic freezes. This heart-breaking incident brought home to me why our planting of a diversified mix of flowers forming sequential mutualisms with particular pollinators is so important. And of course, the provision of water in pools and seeps is especially important to pollinators during seasons or years of extended drought. This humble parable is simply one more way to remind us that what we plant for all kinds of pollinators now matters, more than ever before. So this spring, from the April fourteenth Day of Action and Contemplation for imperiled pollinators to National Pollinator Week, June 16-22, thousands of citizen scientists are planting milkweeds and other native wildflowers in schoolyards, on college campuses, and around churches, synagogues, and mosques. Please join their ranks and show your commitment to making way for monarchs and other imperiled pollinators through tangible actions. |

|