|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The NAPPC Honey Bee Health Task Force The NAPPC Honey Bee Task Force has several functions, determining each year the recipients of honey bee health grants that have for the past four years supported research in honey bee genetics, pesticide exposure, nutrition and management. In addition, the task force is dedicated to providing the latest findings and perspectives on honey bee health to the public, policy makers and the press. The following honey bee health issues have been provided by that task force. We hope you find them useful, and we welcome questions and comments to info@nappc.org. |

Honey Bee Health While honey bees are clearly not the only hard working pollinators that deliver a bounty to humans and other animals, their recent deaths from Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) starting in 2006 have captured the world’s attention. To date, CCD has been defined as a series of symptoms, but the cause and the cure have remained complex and elusive. CCD is not the only problem facing honey bees; in fact, in 2010 the overwintering losses were at the same unsustainable rates of over 30% but the cause seemed to be less from CCD than from other problems. Below is a list of the variety of issues facing honey bees. |

The North American Pollinator Protection Campaign Scientists Report on Honey Bee Stressors

Parasites: |

|

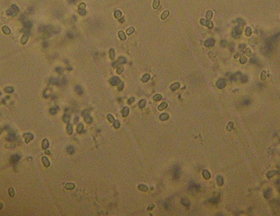

| Nosema ceranae This microscopic fungus can weaken or even kill colonies when the majority of workers become infected. Spores of the fungus survive on wax combs and stored food inside colonies. When workers eat these spores the fungus invades the lining of the intestine. Highly infected bees cannot digest efficiently and die earlier. Beekeepers use antibiotics and disinfection of hives to control this disease. |

|

Viruses

Thus far, more than 20 honey bee viruses have been identified. These viruses can impact bees in multiple ways, including killing developing larvae and pupae, decreasing the lifespan of adult bees, causing spasms and tremors, reducing cognitive skills, and impairing wing development so that bees cannot fly. Most honey bee colonies have multiple viruses, and the levels of these viruses can fluctuate throughout the year. Exposure to other stressors, particularly Varroa parasitization, can immunosuppress bees so that the effects of the viruses are more dramatic. The only treatment for viruses thus far is to feed the colony a solution of virus-specific RNA that enhances the bees' immune responses to these particular viruses, but these treatments only suppress the viral infections, and do not eradicate them. Other approaches that are being investigated include breeding bees with genetic resistance to the viruses. |

|

| Bacterial Diseases: American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae) American foulbrood is an infection that kills young bees (brood) inside the wax cells in which they develop. This dead brood becomes a source of infection spread by workers nursing young brood. Some bees can detect and remove the diseased brood and this stops the disease from spreading. Beekeepers also use antibiotics to prevent the disease. |

|

| Pesticides: Pesticides are usually man made chemicals designed to kill pest organisms, that may injure plants or animals including humans. Pests cause economic damage by reducing crop yields directly or by producing crop, or ornamental plant diseases, or by competing with crops, or by reducing animal and human health, or by damaging buildings and structures. Pesticides are categorized according to their intended use as well as by their chemical composition. Pesticides are widely used and are divided into insecticides/acaricides, used to control insects and mites or ticks, fungicides used to control plant diseases; rodenticides, used to control rodents; and herbicides used to prevent weeds from competing with crops, grasses or ornamental plants. Pesticides usually contain an active ingredient, with a known mechanism for killing the target pests. Pesticides vary widely in their safety to humans and the environment and are sold as a formulation with added ingredients that augment the action of the active material when mixed in water for application. More than 1200 chemicals are registered for use in the United States and are used in some 18,000 separate products sold under a variety of trade names. People who apply the more toxic pesticides must have training and a state issued license to use these materials. Some insecticides have warnings or bee hazards on their label because they are toxic to honey bees, causing honey bee deaths. If the insecticide has a sub-lethal affect on honey bees it may result in reduced larval survival, altered foraging behavior or shortened lifespan of adult bees. The extent of the sub-lethal affects is still unknown. |

|

| Nutrition: Honey bee colonies are healthier and stronger with access to pollen from diverse sources of flowering plants. However, floral diversity in landscapes has been reduced by intensive agriculture (single crops, few flowering weeds, limited hedgerows) and urbanization. In recent years, the pollination of early crops (such as almonds in California in February) has further increased the demand for strong colonies at times of year with few floral sources. Furthermore, changes in climate patterns may also affect seasonal availability of flowering plants. This requires beekeepers to use artificial sources (sugar syrup, corn syrup, and pollen substitutes) to try to meet the increased nutritional demands of their colonies. Varroa mites |

|

| Genetics: Honey bee colonies are headed by a single queen who mates with an average of 12 males, and thus honey bee colonies are extremely genetically diverse. Several studies have demonstrated that genetic diversity improves the disease resistance and productivity of colonies, including their overwintering ability. Furthermore, strains of honey bees can have different traits - some forage for more pollen, while others are more adept at hygienic behavior, in which diseased or parasitized brood is removed. Several breeding programs are underway to develop stocks of bees that are more resistance to diseases and parasites, are better at overwintering in specific climates, and are productive and gentle. |

|

| Queen Quality: The honey bee queen is responsible for producing all the workers in the colony, and she lays up to 1500 eggs a day. Poor quality queens can severely impact colony health. Queens with low egg-laying capacity can limit the numbers of health workers produced, while unhealthy queens can die or be killed by workers, causing a break in brood rearing that again limits colony growth and productivity. Poor quality queens are consistently cited by beekeepers as a major factor underlying colony failure, and a longitudinal study of colonies indicated that loss of a queen or lack of laying by a queen was one of the two factors linked to colony loss. Several factors seems to impact queen quality, including rearing conditions and mating number. |

|

| Management: Proper management of honey bee colonies is a critical component of their health and productivity. Many of the stressors listed on this page can be mitigated by using the proper techniques. Beekeepers need to place their colonies is appropriate locations, which allow access to adequate foraging sites and are distant from areas where pesticides are being applied (honey bees can forage up to 5 km away from their colonies). Beekeepers can provide supplementary nutrition, in the form of sucrose solution or protein patties, during periods of low nectar flow. Beekeepers can monitor for pests, such as Varroa mites and Nosema microporidia, and use chemical or non-chemical methods to control these as needed. Beekeepers can minimize exposure to pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria, by systematically replacing used brood comb with fresh comb. Using genetic stocks of bees that more resistant to pests and pathogens is also an excellent way to reduce complications from these two stressors. Finally, rapid supercedure of poor quality queen honey bees can lead to colony losses, and thus purchases queens from excellent sources or rearing queens locally can improve colony productivity and health. For more information, please see the Honey Bee Best Management Practices guide that has been developed by the Managed Pollinator Coordinated Agriculture Program (CAP) and Project Apis m (PAm): http://www.extension.org/pages/33379/best-management-practices-bmps-for-beekeepers-pollinating-californias-agricultural-crops |

|

Reviews on Honey Bee Health

The Plight of Bees- Environmental Science and Technology

Dennis vanEngelsdorp, Marina Doris Meixner A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 103 (2010) S80–S95

Solving the Mystery of the Vanishing Bees- Scientific American: April 40-47.

Nosema ceranae The Inside Story

Nosema Microsporidia: Friend Foe and Intriguing Creatures

Higes M, Martín-Hernández R, Botías,C, Garrido-Bailón E, González-Porto AV, Barrios L, del Nozal MJ, Bernal JL, Jiménez, JJ, García-Palencia, P, Meana, A. 2008

Honey Bee Disorders: Bacterial Diseases

Honey Bee Nutrition

UNEP EMERGING ISSUE- Honey Bee Colony Disorders and Other Threats to Insect Pollinators

Download this PDF to learn more about global Honey Bee colony disorders and other threats to insect pollinators.

"Introduction

"Introduction

Current evidence demonstrates that a sixth major extinction of biological diversity event is underway.1. The Earth is losing between one and ten percent of biodiversity per decade2, mostly due to habitat loss, pest invasion, pollution, over-harvesting and disease3. Certain natural ecosystem services are vital for human societies. Many fruit, nut, vegetable, legume, and seed crops depend on pollination. Pollination services are provided both by wild, free-living organisms (mainly bees, but also to name a few many butterflies, moths and flies), and by commercially managed bee species. Bees are the predominant and most economically important group of pollinators in most geographical regions. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO)4 estimates that out of some 100 crop species which provide 90% of food worldwide, 71 of these are bee-pollinated. In Europe alone, 84% of the 264 crop species are animalpollinated and 4 000 vegetable varieties exist thanks to pollination by bees5. The production value of one tonne of pollinator-dependent crop is approximately five times higher than one of those crop categories that do not depend on insects. Has a “pollinator crisis” really been occurring during recent decades, or are these concerns just another sign of global biodiversity decline? Several studies have highlighted different factors leading to the pollinators’ decline that have been observed around the world. This bulletin considers the latest scientific findings and analyses possible answers to this question. As the bee group is the most important pollinator worldwide, this bulletin focuses on the instability of wild and managed bee populations."

Excerpts from the PDF

A Message from the Executive Director on CCD and Neonicotinoids

Many newspapers and online journals have reported that a major step forward has been made in the research to unravel to mysterious disappearance and death of honey bees called Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). The assertion that CCD has been solved, however, is premature. A recently released study has identified a link between the presence of both fungus and virus in the dead bees sent to the researchers to examine for the disorder. However, the researchers themselves are unclear about the exact form of the virus or whether this relationship between the presence of both fungal and viral elements is the cause or the effect of CCD. The true significance of the findings has yet to be defined. Unfortunately, the results of this study have been distorted through what are usually reliable media sources. Media claims of a solution to CCD are, regrettably, exaggerated. Far from proclaiming that CCD is solved, news reporting should have signaled a new and potentially important step forward in the search for answers. Further adding to the confusion, the overwintering death rates for honey bees have continued at the same unsustainable and disturbing rate this year, but the cause of these deaths seems to be shifting AWAY from traditional CCD symptoms. In short, exaggerated claims help no one, especially not bees. At a time when there are thousands of critical issues clambering for attention, declaring a premature fix for a highly complex situation is tantamount to condemning honey bees to less attention, research and real solutions to their plight. Keeping perspective on results, demanding exacting science that withstands challenges, insisting on comprehensive and accurate reporting, and basing a prudent course on replicable science is the only way to ensure the future for honey bees, pollinators and the humans who depend on them. While important research continues to unlock new clues, the beekeeping and research communities agree that this moment continues to be critical for the health of honey bees and all pollinators, and the mystery of CCD remains both complex and elusive.

|

|

Honey Bee and Wild Bee Interaction Updated April 2, 2012 – www.pollinator.org The following list of peer reviewed publications has been generated by members of the pollinator LISTSERV. Some of these studies report tests of native bee/honey bee interactions, others provide background and insight into potential interactions. If you have an additional study to add to this list please email info@pollinator.org. We are also in the process of developing a new 2012 NAPPC Task Force that will take on this issue. If you are interested in chairing or participating in this task force please contact Vicki Wojcik, vw@pollinator.org. |

|

Peer Reviewed Publications

Reports and other resources