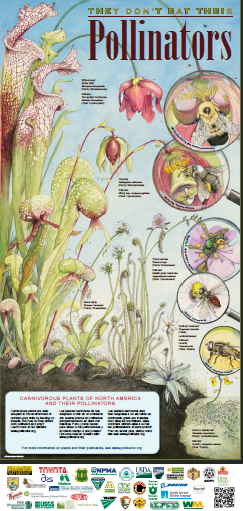

Carnivorous Plants of North America

Overview

Carnivorous plants have fascinated scientists and nature enthusiasts for centuries. In 1875 Charles Darwin wrote one of the first popular books on this fascinating group of plants, Insectivorous Plants, which looked at the adaptations of these plants that allow them to live in nutrient-poor habitats. Carnivorous plants absorb nutrients from trapped insects by dissolving and digesting their prey.

While much has been studied since then on their feeding mechanisms, surprisingly few studies have examined the pollination biology of carnivorous plants. How do carnivorous plants attract both pollinator and prey? One attraction lures arthropods into a trap where the plant digests the prey, while the other attraction entices insects to carry pollen from their flowers to other plants without killing them. Natural selection has led to amazing adaptations, which have evolved independently in a number of plant lineages.

Three main mechanisms alleviate pollinator-prey overlap: spatial separation of flowers and traps, temporal separation of flowers and traps, and specific attractions to flowers and traps. Spatial separation occurs when the flowering structures are physically situated well away from the traps. Most often, the traps lie close to the ground (or underwater, as is the case of bladderworts), while the flowers bloom high atop a stalk called a scape. Temporal separation occurs when the flowers bloom at a different time before the traps develop, preventing pollinators from encountering the traps. Another mechanism occurs when flowers and traps use different attractants to lure insects: specific guidance such as UV patterns, having the traps appear unattractive to flower-visiting insects, or having the flowers appear unattractive to the prey. These attractants take the form of color, odor, or rewards (nectar, pollen, or oils).

Unfortunately, the public’s fascination with carnivorous plants has led to the poaching and over-collecting of these remarkable plants from their native habitats. Many carnivorous plants are now listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species or on government endangered species lists. Some carnivorous plant taxa are also listed by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), aimed at ensuring that the international trade of wild plants does not threaten the survival of the species in the wild. To help protect these species, please don’t pick the plants or try to transplant them. Refrain from buying specimens that may be wild-collected; only buy plants or seeds that you know were grown in a greenhouse or by cloning potted plants.

Carnivorous Plants Identification

1. White-topped Pitcher Plant - Sarracenia leucophylla (Sarraceniaceae)

- Geographic Distribution: Southeastern Mississippi to western Florida. Once thought to be extinct in Georgia (once occurring in five counties), a privately-owned site was detected in 2001.

- Pollinators: Bumble bees (Bombus), sweat bees (Augochlorella), and flies (Flecherimyia fletcheri) are known to pollinate Sarracenia species.

- Habitat: Seepage areas and savanna bogs.

- Size: Pitcher size is as large as 1 m, while diminutive forms (30 cm) are seldom seen. The top third of each pitcher is pigmented white.

- Insect Trap: The leaves take the form of a pitcher. Insects are attracted by the color, scent, and nectar-like secretions on the lip of the pitchers. Inside the pitcher are downward pointing hairs that make retreat by captured prey challenging. The bottom of the pitcher is filled with fluid containing digestive enzymes and bacteria.

- Bloom Period: Early spring before small spring pitchers, followed by non-carnivorous flat leaves in midsummer and robust pitchers in early autumn.

- Flowers: Deep maroon petals.

- IUCN threat status: Vulnerable (VU). Current threats include loss and degradation of wetland habitat, roadside herbicide usage, invasive exotic species (such as kudzu, Chinese privet, and Japanese honeysuckle), and collecting for horticultural trade. Listed on CITES Appendix II.

- Encyclopedia of Life: http://eol.org/pages/584635/overview

Sarracenia leucophylla flowers are held singly on long stems. The structure of the flower prevents self-pollination, thus requiring pollinators to transfer pollen to other flowers. As the nectar-searching pollinator enters the flower, which hangs upside-down, the insect must pass a stigma to enter the flower chamber formed by the style. Inside the chamber, the insect comes into contact with pollen from both hanging anthers and the umbrella-like style which catches dropped pollen. When the insect exits the chamber, it must force its way under a petal, away from the stigma and preventing self-pollination of the flower. In Sarracenia, a temporal separation of flowers and traps exist, in which the flowers reward pollinators with pollen and nectar a month before the plants produce the carnivorous pitchers.

|

back to the top

2. Cobra Lily, California Pitcher Plant - Darlingtonia californica (Sarraceniaceae)

- Geographic Distribution: Southwestern Oregon and northern California.

- Pollinators: Solitary bees (Andrena nigrihirta).

- Habitat: Found in sphagnum bogs, slowly draining bogs, seeps, marshy meadows, and along trickling streams.

- Size: Pitcher size is often between 20 and 60 cm tall, but may vary from 1 cm to over 1 m. The tubular leaves resemble a rearing cobra, contributing to its common name “cobra lily.”

- Insect Trap: Each leaf takes the form of a “pitcher” with a hood that arches over the mouth. Insects are attracted to the color, scent, and nectar glands that cover the hood. The inner walls of the hood have short, stiff, backward-pointing hairs.

- Bloom Period: Early spring before new leaves appear. From April to August depending on altitude.

- Flowers: Large, showy, sweetly fragrant. Yellowish purple with five green sepals. Abundant pollen.

- IUCN threat status: Lower Risk/least concern (LR/lc). Current threats include habitat destruction and collecting for horticultural trade (domestically and internationally).

- Encyclopedia of Life: http://eol.org/pages/584644/overview

Darlingtonia californica is the only species in the genus Darlingtonia. Little is known about the pollination biology of this species. Regular floral visitors included thrips and several species of spiders, but it is unknown whether they actively carry pollen to other flowers. A published account of a generalist solitary bee, Andrena nigrihirta, which was observed visiting and pollinating D. californica flowers at five different sites in northern California (Meindl and Mesler, 2011), suggests that it is one of the most likely pollinators of this plant species. |

back to the top

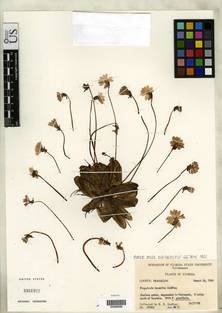

3. Tracy's Sundew - Drosera tracyi (Droseraceae)

- Geographic Distribution: South-central Georgia and panhandle Florida to eastern Louisiana.

- Pollinators: Sweat bees (Agapostemon), bumble bees (Bombus), syrphid flies, and meloid beetles.

- Habitat: Wet sand, pond margins in pinelands, exposed lake bottoms, and raised bogs.

- Size: Leaf length is 25-50 cm. Scapes grow to 25-60 cm tall.

- Insect Trap: The erect, tall, filiform leaves are covered in sticky glandular hairs. The hairs produce digestive juices that decompose trapped prey.

- Bloom Period: April through June.

- Flowers: Pink to light purple, rarely white.

- IUCN threat status: Not yet assessed. NatureServe assesses this species as G3 Vulnerable.

- Encyclopedia of Life: http://eol.org/pages/481344/overview

Sundews are found on every continent except Antarctica. Often considered a variety of Drosera filiformis, this species is the only Drosera endemic to the USA. Several species of Drosera are self-compatible and/or are able to self-pollinate and self-fertilize autonomously. It is hypothesized that the flowers on long peduncles evolved not to separate the traps and flowers but to project their flowers well above ground level to attract flying insects that serve as pollinators.

|

back to the top

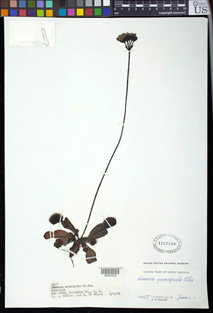

4. Godfrey's Butterwort, Violet Butterwort - Pinguicula ionantha (Lentibulariaceae)

- Geographic Distribution: Central panhandle region of Florida, with most sites having very few individuals.

- Pollinators: Possibly bees and flies.

- Habitat: Open, acidic soils of seepage bogs on gentle slopes, deep quagmire bogs, ditches, and depressions in grassy pine flatwoods and grassy savannas, often occurring in shallow standing water.

- Size: Rosettes are about 15 cm across. Scapes grow to 10-15 cm tall.

- Insect Trap: The leaves are coated with glandular hairs that secret sticky mucilage. Insects become trapped when they mistake the sticky mucilage for water or nectar. The edge of the leaf slowly rolls over the insect while it is digested.

- Bloom Period: February through April.

- Flowers: Corollas are pale violet to white, with a deep violet throat and dark veins.

- IUCN threat status: Not yet assessed. Listed as Threatened by the US Endangered Species Act. NatureServe assesses this species as G2 Imperiled. The species' habitat is declining in extent and quality due to logging, shading by planted pines, and drainage alteration.

- Encyclopedia of Life: http://eol.org/pages/475532/overview

Of the roughly 80 currently known species of Pinguicula, just about 50 percent are found in Central America. A strong spatial separation of flowers and traps exist in butterworts. The flowering stalks extend high above the sticky rosette of fungal-scented leaves. A wide range of insects have been seen visiting the flowers of Pinguicula species, including beeflies (Bombylius), bees (Andrena, Anthophora, Bombus, Halictus, Lasioglossum, Osmia), hawkmoths, butterflies, calliphorid flies, small beetles and thrips. The literature is lacking in pollination biology studies of Pinguicula ionantha, a threatened species restricted to a small area in northwestern Florida. An online photograph shows a flower visited by a species of hoverfly in the genus Toxomerus.

|

back to the top

5. Common Bladderwort - Utricularia macrorhiza (Lentibulariaceae)

- Geographic Distribution: Throughout Canada and the continental United States. In Mexico, found in Baja California and Coahuila.

- Pollinators: Possibly bees and flies.

- Habitat: Shallow waters of lakes, ponds, bogs, marshes, and fens.

- Size: Flowers bloom atop a 5-25 cm scape.

- Insect Trap: Underwater bladders have a small opening sealed by a hinged door with trigger hairs. When aquatic invertebrates touch the hairs, the door releases a suction pulling the invertebrate into the bladder, where enzymes digest the victim.

- Bloom Period: June through August.

- Flowers: Yellow, sometimes pink or purple.

- IUCN threat status: Not yet assessed. NatureServe assesses this species as G5 Secure.

- Encyclopedia of Life: http://eol.org/pages/39917466/overview

Utricularia is the largest genus of carnivorous plants, with more than 220 species, occurring on all continents except for Antarctica. It is free-floating and lacks roots. Bladderworts exhibit perfect spatial separation of flowers and traps, as the flowers bloom well above the water while the traps grow underwater. Even though Utricularia macrorhiza is far-ranging, the literature is lacking in pollination biology studies and reports of pollinator observations. An online photograph shows flower visitations by Helophilus intentus.

|

back to the top

6. Venus Flytrap - Dionaea muscipula (Droseraceae)

- Geographic Distribution: North Carolina and South Carolina.

- Pollinators: Possibly small flies and beetles.

- Habitat: Depressions in wet pine flatwoods and wet pine savannas.

- Size: The flower stalk reaches up to 30 cm.

- Insect Trap: The leaf blades terminate in bivalve traps with sharply toothed edges. Green on the outside, red pigment shades the insides of the trap where trigger hairs, when touched, cause the leaf to snap shut trapping its prey.

- Bloom Period: May through June.

- Flowers: Small white flowers with faint green veins.

- IUCN threat status: Vulnerable (VU). The species has a requirement for frequent natural fires and an open understory. Habitat alteration and fire suppression are the largest threats. Listed on CITES Appendix II.

- Encyclopedia of Life: http://eol.org/pages/584643/overview

Even though the Venus flytrap is perhaps the best-known carnivorous plant species, very little has been published about pollination of this species in the wild. There is a clear spatial separation of the flower atop tall scapes and the traps. The diet of Dionaea is limited to crawling arthropods such as ants, spiders, and beetles, while a very small percentage of its diet is flying insects. Though the plant is self-compatible, a 1958 report suggests that pollination is carried out by “various beetles, small flies and possibly spiders.” NatureServe reports that a rare critically imperiled moth, the Venus Flytrap Cutworm Hemipachnobia subporphyrea, specializes as a herbivore on the plant. More research on the pollination biology of this remarkable species is clearly needed.

|

back to the top